As an athlete who practically lived in a physical therapy clinic for over 10 years, then a clinical social worker and childbirth educator who worked in the New York City hospital system for close to 12 years, and now a psychotherapist focusing on athlete mental health across diverse sports and backgrounds, I am keenly aware of the relationship between sports and medicine.

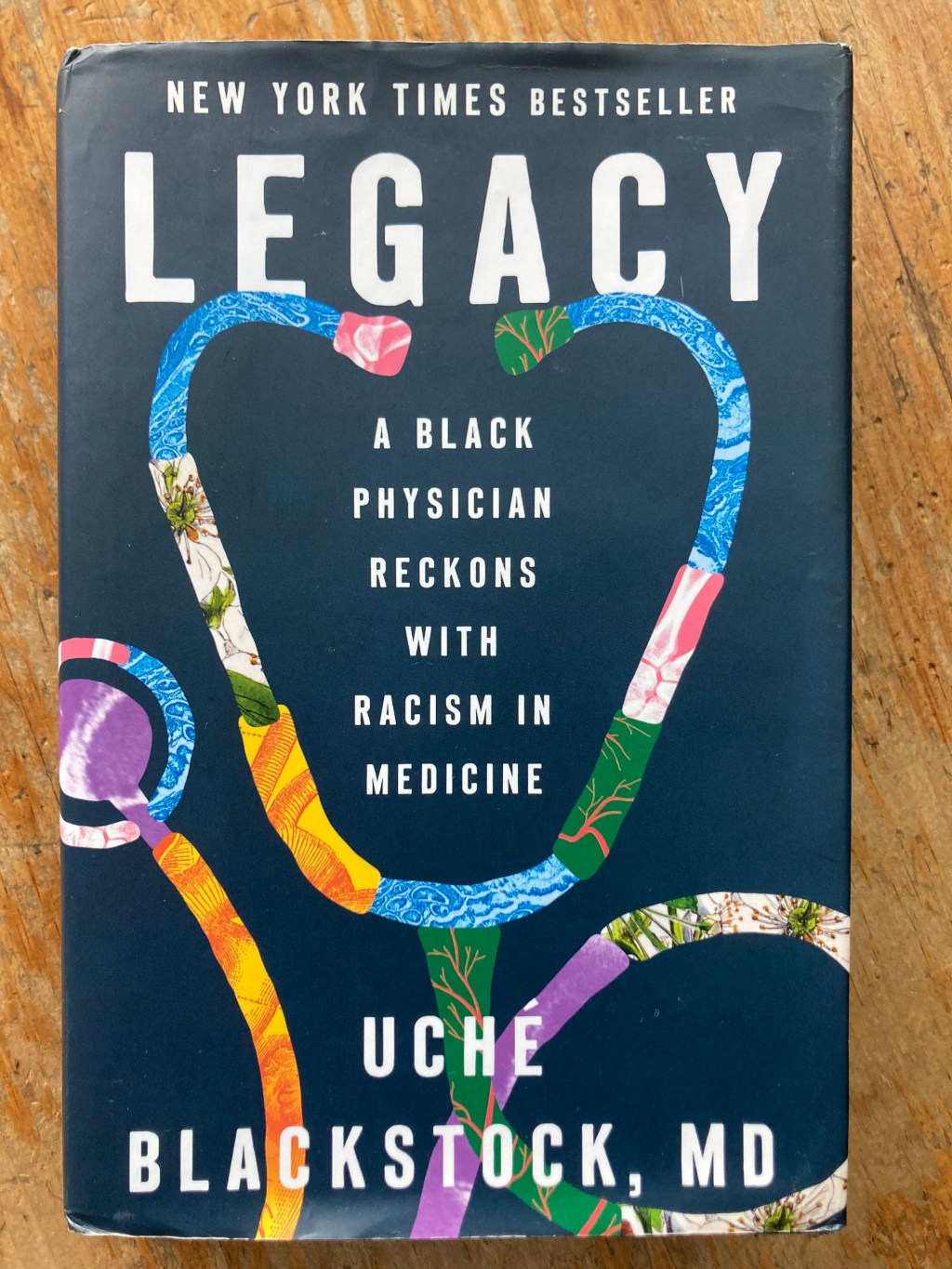

This unique trajectory through healthcare and athletics gave me a multifaceted lens through which to read Dr. Uché Blackstock’s Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine – a memoir that resonated with me on both professional and personal levels. Having witnessed healthcare disparities from multiple angles – as a patient, a provider within the system, and now as a mental health professional supporting athletes – Blackstock’s unflinching examination felt both validating and urgently necessary.

Her narrative arrives at a critical moment when conversations about racial and gender disparities in healthcare intersect powerfully with similar reckonings happening across sports. Having spent years in the city hospital system, I recognize the systemic issues she identifies. Having also been an athlete dependent on medical providers to keep my body functioning, I understand how these disparities can determine athletic trajectories. The trust between athlete and medical provider is sacred, yet especially for Athletes of Color, child athletes, and women athletes, that relationship can be compromised before it begins.

What particularly struck me was Blackstock’s documentation of how medical biases affect diagnosis, treatment, and patient-provider relationships. In combination with the longstanding sports ideology of “no pain, no gain,” the reality that most athletes live with some kind of ongoing “minor” injury (e.g., mild tendonitis), and the lack of research concerning the unique impact of sports on women and children’s bodies (versus men’s bodies, which most athlete development research is based on), I see how these biases can further complicate whether an athlete’s pain is taken seriously, how injuries are treated, how careers evolve, and ultimately, the quality of life of a retired athlete (e.g., chronic medical and mental health conditions). The data she presents on pain management (showing how Black patients are systematically undertreated for pain) explains patterns I’ve observed throughout my entire career, from physical therapy clinics to professional training facilities.

For anyone working at the intersection of sports, health, and performance, Legacy offers critical insights that will improve how we serve all people, let alone athletes.

Beyond the professional applications, Legacy is simply a beautiful and powerful human story of perseverance, purpose, and the courage to stand up – qualities we need in athletics and institutions in order to improve health, mental health, and wellbeing for all.

I’ve been recommending this book to everyone I know. Add it to your collection, it’s that essential.

All the best,

Laura

Note: This and every Athlete Illuminated post is for educational purposes only and not a replacement for mental health treatment. If you are in urgent need of mental health support, please call 9-8-8. If you are experiencing an emergency, please call 9-1-1 or go to your nearest emergency room. For ongoing mental health concerns, consider seeking professional support or therapy.

Leave a comment